The chemist and druggist, 15. September 1859

9/106

- Publication/creation

- London : Morgan Brothers, 1859-

- Contributors

- United Business Media.

- Copyright note

- UBM.

- Type/technique

-

Electronic journals

Periodicals

- Subjects

-

Pharmacy

Drug Industry

Great Britain

- Attribution and usage

-

Wellcome Collection

You have permission to make copies of this work under a Creative Commons, Attribution, Non-commercial license.

Non-commercial use includes private study, academic research, teaching, and other activities that are not primarily intended for, or directed towards, commercial advantage or private monetary compensation. See the Legal Code for further information.

Image source should be attributed as specified in the full catalogue record. If no source is given the image should be attributed to Wellcome Collection.

The image contains the following text:

SCHOOLS Or CHEMISTUY.

There probably never was a period when the spirit of competition in the commercial world

existed to such an extent as at the present time. Invention follows invention, and there is

scarcely a day that some new process or article of utility is not brought to light, or that those

already in existence do not undergo some improvement, rendering them more adapted for the

purposes for which they were originally intended. In the scientific world also, discoveries are

matters of almost daily occurrence, and there is no branch of science that has experienced

greater changes, or made more rapid progress within the last century, than that of chemistry.

Formerly looked upon with suspicion, and somewhat of dread in the time of the alchemists, it

has been gradually developing its hidden truths, until, in the present age, there is scarcely a

change in nature, or process in the arts, in which chemistry does not play a most important

part.

Education has also been advancing with rapid strides, and much has been said and written

upon the subject. The metropolis abounds with institutions and schools, where the languages

are taught, and lectures delivered on scientific and other subjects ; and innumerable opportu-

nities are afforded to those who arc willing to take advantage of them.

Most of the metropolitan colleges have laboratories where practical chemistry is taught,

assisted by courses of lectures by eminent professors. Of these, none have contributed more in

raising the status of the Chemist and Druggist, and affording the means of improvement at

a moderate outlay, than the Pharmaceutical Society ; and the exertions of this body have been

as successful as could be expected, until invested with full authority by Government,

On the younger branches of the trade the future status will much depend ; and by doing all

they can to improve their education, by taking advantage of such opportunities of improvement

as present themselves, they will not only benefit themselves, but assist in raising the status of

the body to which they belong.

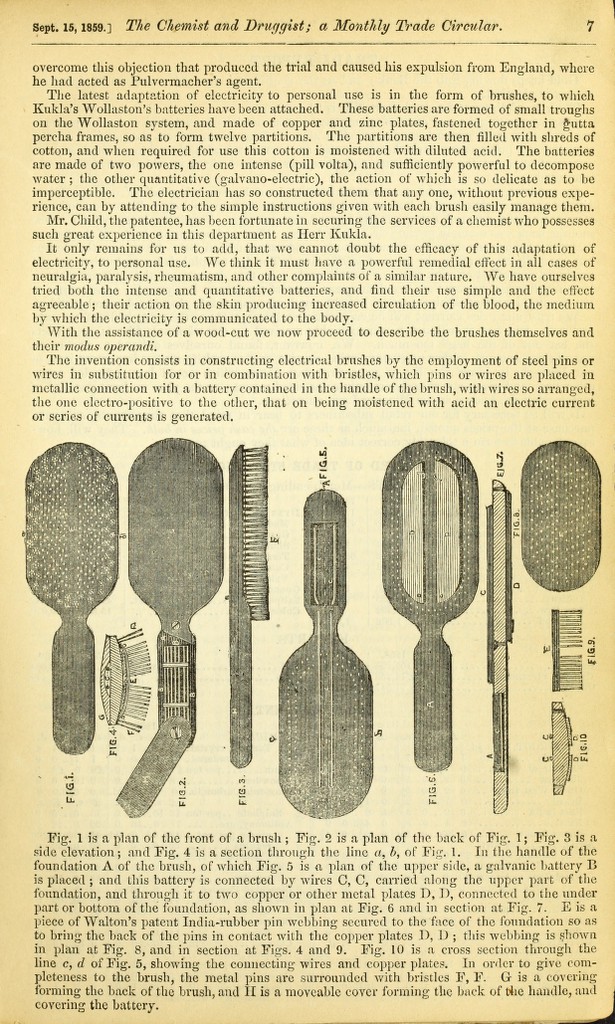

GALVANO-ELECTRIC BRUSHES.

Our readers will hardly require to be informed that electricity is by no means a newly-dis-

covered power, nor indeed is its application to brushes altogether new. Griffiths, the inventor

of the screw propeller, having patented it in 1852, although from various causes, principally its

complications, he never practically carried out this patent. Herring, again, by placing

a magnet at the back, has produced a magnetic brush which appears to have commanded a

very large sale ; indeed, we perceive he has just renewed the patent (Sept. 7th). As that

necessitates the payment of a further fee of £50, this adaptation of magnetism appears to have

been very successful.

Francis X. Kukla,* a Viennese chemist, has just invented a mode of applying this power

to brushes, which, combining as it does, the necessary qualities of simplicity and effectiveness,

is found to succeed; therefore we think that a few remarks on the subject of galvanism, and

explanatory of its application to the brushes, which are patented as " Child's Galvano-clectric,"

will be acceptable at this moment, the more especially as they are now being introduced

to the notice of the public, and our readers will doubtless find it advantageous when selling

them, to be able to give some account of the principles on which their action depends.

The Greek philosophers first discovered that by rubbing amber (succinum in Latin, EAe/crpov

in Greek), a power was produced capable of attracting light bodies. From this Greek word

electron, the term electricity is derived. In 1786, the now celebrated Galvany, then a professor

in the university of Bologna, discovered that various metals when placed in contact with

animal matter produced, to his great astonishment, visible electric shocks. It remained

however for Volta, another Italian professor, to prove that what had astonished Galvany and

his compeers, was nothing but the electricity produced by the contact of different metals.

Volta and others, notably Wollaston, greatly developed the newly-found power, but our own

countryman, Davy, was the first to produce a battery of sufficient power to decompose alkalies

and earths in metals.

Becquerel, Daniel, Smee, and others, by their experiments have since his day made further

improvements, by the construction of double-fluid batteries—the use of the higher negative

silver in the place of copper, &c«

Later still, platinum, carbon, and antimony, all highly negative bodies, have superseded other

negatives for double-fluid batteries, and are used in conjunction with the positive metal zinc.

Meantime experiments, having medical purposes in view, were made with this powerful

agent, and amongst other inventions in this direction, IViYermacher's chainsi for application

to the body have been found to succeed in removing nervous and other similar' complaints. A

great drawback, however, arose from the heat of the body causing these to become dry, the

power depending upon their being kept moist—and it was an attempt on the part of Meinig to

* Chemist to the Bank of Austria, at present residing in this country.